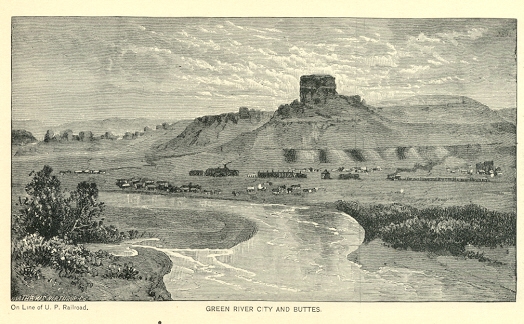

Green River City, 1876

Compare above photo with 1907 on next page.

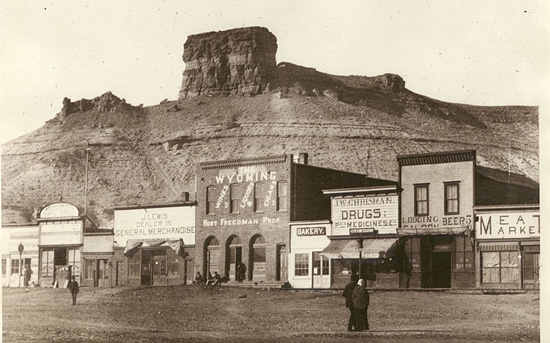

Green River City, approx. 1890

Green River City, now Green River, the third

place of the same name in Wyoming, was founded with the arrival of the

railroad in 1868 when the area was still a part of

Dakota Territory. The first business was that of Jake Field who operated a store, hotel and

rstaurant, as depicted in the next photo. Field, along with H. M. Hook, previously mayor of

Cheyenne, and James Moore, anticipated that the railroad would establish a division point there. Unfortunately,

the three forgot that the railroad was essentially a real estate business. Its

division points were located in towns established by it, such as Cheyenne, Laramie City, and

later Evanston, where the railroad would reap the benefits of lots sales, not third persons. Thus,

while the railroad was passing through, Green River City grew to an estimated 2,000. The population precipitously

dropped to less that 150 after an advertisement appeared in the

Frontier Index:

BRYAN

The

Winter Town, UPRR

Bryan is located on Black's Fork on the line of the

UPRR and will be the terminus of the Railroad for freight

and passengers during the coming winter, and probably until

the connection is made between the UPRR and the Central PRR.

Bryan is the most accessible point to the Sweetwater mines,

and will unquestionably be

The Best Town

for trade between Omaha and Salt Lake City. Large machine

shops and a Round house will be built there immediately.

Now is the time to purchase lots at the low valuation

placed on them by the Railroad company

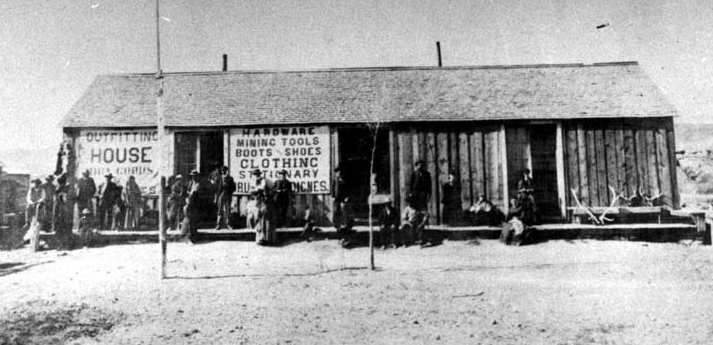

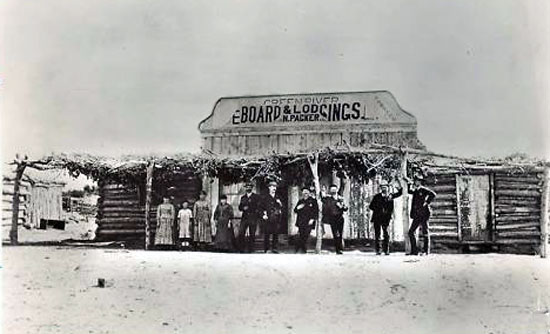

Jake Field's Store, approx. 1871

George A. Crofutt in his 1871 Crofutt's Trans-Continental Guide explained

the effect on Green River City:

This now deserted city was laid out about the first of July, 1868, by H.M.

Hook, first Mayor of Cheyenne City. In this enterprise, James Moore, of

Cheyenne, was interested, and these gentlemen suppose that the terminus

of the road would be at this point during the winter. In September, 1868,

the place had a population of over 2,000, and substantial adobe buildings

were erected, and the town presented a permanent appearance. But the river

was bridged and as the road stretched away to the westward, the town

declined as rapidly as it arose, the people moving on to Bryan, Bear River,

and other points, until there was no one left but those connected with the

stations-in the company's employ. The walls of the old buildings are still

standing, some with the roofs still covering them.

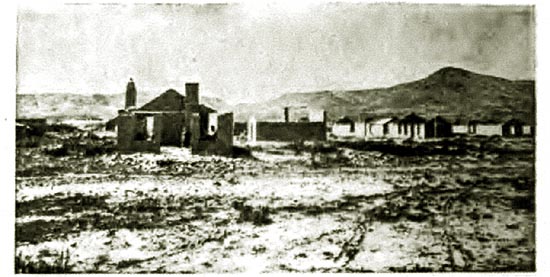

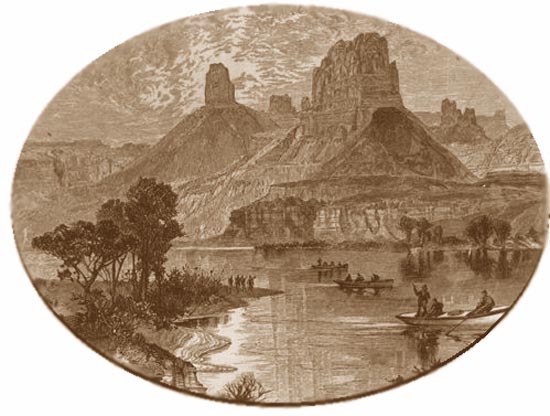

Green River, 1871, photo by E. A. Beaman.

Field arrived from Colorado where he had worked in the express

business in the gold fields. The two Powell Expeditions, which put in from Green

River City, purchased some of its supplies from Field. The first (1869) Powell Expedition

had to await the arrival of equipment. While waiting, the members entertained themselves with liquid refreshment purchased

from Field. As described by John C. "Jack" Sumner (1834-1902), a member of the first expedition from

Middle Park, Colorado:

"We reached Fort Badger [sic], and then on to Green River Station on the Union Pacific

railroads where we camped and awaited orders and in the meantime tried

to drink all the whiskey there was in town. The result was a failure, as

Jake Field persisted in making it faster than we could drink it."

The Company for the first expedition was made up primarily of trappers, hunters, and

army veterans. Powell in his Canyons of the Colorado described the crew:

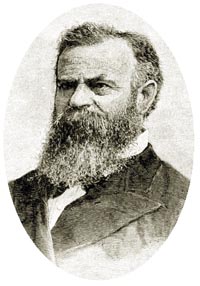

John Wesley Powell, woodcut, 1895

J. C. Sumner and William H. Dunn are my boatmen in the "Emma Dean"; then

follows "Kitty Clyde's Sister," manned by W. H. Powell and G. Y. Bradley;

next, the "No Name," with O. G. Howland, Seneca Howland, and Frank Goodman;

and last comes the "Maid of the Canyon," with W. E. Hawkins and Andrew Hall.

John Wesley Powell, woodcut, 1895

J. C. Sumner and William H. Dunn are my boatmen in the "Emma Dean"; then

follows "Kitty Clyde's Sister," manned by W. H. Powell and G. Y. Bradley;

next, the "No Name," with O. G. Howland, Seneca Howland, and Frank Goodman;

and last comes the "Maid of the Canyon," with W. E. Hawkins and Andrew Hall.

Sumner was a soldier during the late war, and before and since that time

has been a great traveler in the wilds of the Mississippi Valley and the

Rocky Mountains as an amateur hunter. He is a fair-haired, delicate-looking

man, but a veteran in experience, and has performed the feat of crossing

the Rocky Mountains in midwinter on snowshoes. He spent the winter of

1886-87 in Middle Park, Colorado, for the purpose of making some natural

history collections for me, and succeeded in killing three grizzlies,

two mountain lions, and a large number of elk, deer, sheep, wolves,

beavers, and many other animals. When Bayard Taylor traveled through

the parks of Colorado, Sumner was his guide, and he speaks in glowing

terms of Mr. Taylor's genial qualities in camp, but he was mortally

offended when the great traveler requested him to act as doorkeeper at

Breckenridge to receive the admission fee from those who attended his

lectures.

Dunn was a hunter, trapper, and mule-packer in Colorado for many years.

He dresses in buckskin with a dark oleaginous luster, doubtless due to

the fact that he has lived on fat venison and killed many beavers since

he first donned his uniform years ago. His raven hair falls down to his

back, for he has a sublime contempt of shears and razors.

Captain Powell was an officer of artillery during the late war and was

captured on the 22d day of July, 1864, at Atlanta and served a ten months'

term in prison at Charleston, where he was placed with other officers under

fire. He is silent, moody, and sarcastic, though sometimes he enlivens

the camp at night with a song. He is never surprised at anything, his

coolness never deserts him, and he would choke the belching throat of a

volcano if he thought the spitfire meant anything but fun. We call him _

"_Old Shady."

Bradley, a lieutenant during the late war, and since orderly sergeant in

the regular army, was, a few weeks previous to our start, discharged,

by order of the Secretary of War, that he might go on this trip. He is

scrupulously careful, and a little mishap works him into a passion, but

when labor is needed he has a ready hand and powerful arm, and in danger,

rapid judgment and unerring skill. A great difficulty or peril changes the

petulant spirit into a brave, generous soul.

O. G. Howland is a printer by trade, an editor by profession, and a

hunter by choice. When busily employed he usually puts his hat in his

pocket, and his thin hair and long beard stream in the wind, giving him

a wild look, much like that of King Lear in an illustrated copy of

Shakespeare which tumbles around the camp.

Seneca Howland is a quiet, pensive young man, and a great favorite with

all.

Goodman is a stranger to us--a stout, willing Englishman, with florid

face and more florid anticipations of a glorious trip.

Billy Hawkins, the cook, was a soldier in the Union Army during the war,

and when discharged at its close went West, and since then has been

engaged as teamster on the plains or hunter in the mountains. He is

an athlete and a jovial good fellow, who hardly seems to know his own

strength.

Hall is a Scotch boy, nineteen years old, with what seems to us a

"secondhand head," which doubtless came down to him from some knight

who wore it during the Border Wars. It looks a very old head indeed,

with deep-set blue eyes and beaked nose. Young as he is, Hall has had

experience in hunting, trapping, and fighting Indians, and he makes the

most of it, for he can tell a good story, and is never encumbered by

unnecessary scruples in giving to his narratives those embellishments

which help to make a story complete. He is always ready for work or

play and is a good hand at either.

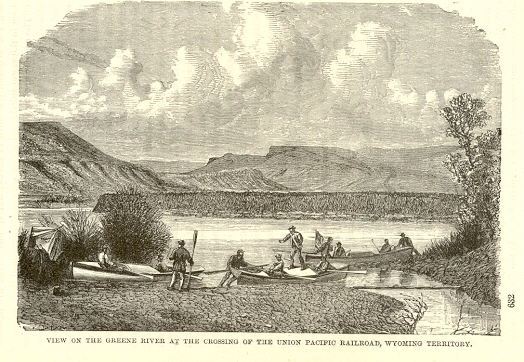

Green RiverStation, "The Start," woodcut from Powell's Canyons of the Colorado, 1895

But, perhaps, the consumption of the

whiskey was as a result of the quality of the coffee. A young Easterner who had been invited to

join the expedition by Powell arrived. The Easterner was particular about the food and

griped for three days. In a 1907 letter to Robert Brewster Stanton, the company's cook,

William Rhodes "Billy" Hawkins described how they got rid of the tenderfoot.

One of the men, Captain W. H. Powell, had a new pair of boots. The coloring from

the leather had impermeated Captain Powell's socks. He requested Hawkins to

boil the socks. Hawkins placed the socks in a small kettle on the stove behind the large coffee

pot, so that it could not be seen. At the noon lunch, Jack Sumner commented that

there was something peculiar about the coffee. Hawkins described the scene:

I took my bowie knife and stuck it in one of the Captain's socks and held it

up over the kettle just back of the coffee. With the reddish brown water

running off, it looked just as though I had taken it out of the coffee

kettle. I yelled "Who in hell put his socks in the coffee?" All said they

had not, except the young man, who did not answer. When I asked him if

he had, he said very politely that he had not, but he was getting up and

leaving at the time. That was the last we ever saw of him.

Later the tenderfoot, wrote Powell telling him that he had a "hard" group about him.

[Writer's note: Robert Brewster Stanton was a railroad and mining engineer who surveyed the

Grand Canyon in 1889-1890.]

Green River City, 1888

As indicated above, by the time of the Second Powell Expedition, Green River City had

seen better days. Frederick Samuel Dellenbaugh (1853-1935), a member of the second (1871)

Expedition, in his 1902 book "The Romance of the Colorado River," described the 1871 appearance

of the town:

"This Place, when the railway was building, had been for a considerable time the terminus and

a town of respectable proportions had grown up, but with the completion of

the road through this region, the terminus moved on, and now all that was to

be seen of those golden days was a group of adobe walls, roofless and

forlorn. The present 'City' consisted of about thirteen houses, and some of

these were of such complex construction that one hesitates whether to

describe them as houses with canvas roofs, or tents with board sides."

The lodging facilities were hardly better.

Green River Lodging Facililties, approximately 1871.

Dellenbaugh in his A Canyon Voyage described them:

For sleeping quarters we were isposed in two vacant

wooden shanties about two hundred yards apart and a somewhat greater distance from the

cook-camp. These shanties were mansions left over, like a group of roofless adobe ruins near by, from

the opulent days of a year or wo back when this

place had been the terminus of the line during building operations. Little remained of its shilom grandeur; a section house,

a railway station, a number of canvas-roofed domiciles, Field's "Outfitting Store," and

the aforesaid shanties in which we secured refuge, being about all there was of the place.

Powell Expedition at Green River, Wyo. Terr., 1871. Engraving based on

photograph attributed E. O. Beaman, see below.

As noted with regard to Sherman, 19th century engravers often

based their work on existing photographs, nor was it uncommon for photographers to take credit for photographs

that they did not personally take. This 1875 engraving was

based on an earlier 1871 photograph of the second Powell Expedition putting in to the Green River near

the Railroad Bridge with, however, some artistic changes.

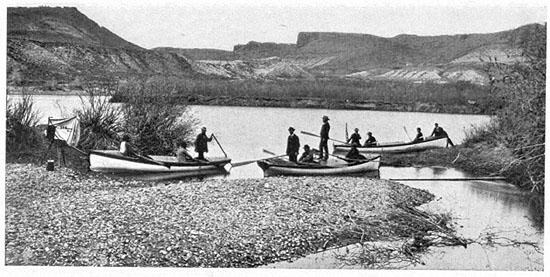

Powell Expedition, May 1871, photo attributed to E. O. Beaman.

Identification as provided by Frederick S. Dellenbaugh,

A Canyon Voyage G. P. Putnam's Son's, 1908, L to R.:

In first boat, the

Canonita, E. O. Beaman (expedition photographer), Andrew Hattan, Walter Clement Powell;

In second boat,

the Emma Dean, Steven Vandiver Jones, John K. Hillers (later assistant

photographer and chief photographer [see text below]), John Wesley Powell,

Frederick S. Dellenbaugh (artist and topographer);

In third boat, the Nellie Powell,

Almon Harris Thompson, John F. Steward, Francis Marion Bishop, and Frank Richardson.

As noted, photogaph is commonly attributed

to expedition photographer E. O. Beaman. See back of stereograph of the scene reproduced below. Beaman, however is, as noted, in one of the

boats and, therefore, could not have taken the particular picture. Missing from the scene is assistant photograper J. Fennemore who did not join the

expedition until March 19 at Pipe Springs.

No one from the expedition is missing from the scene. The mystery is, therefore, who took the picture.

It has been suggested that Beaman set up the scene, prepared the glass plate in the dark box to the left of the

Canonita, placed the plate in the camera, and gave instructions possibly to Jake Field on the timing and removal and replacement of the

lens cap. Beaman would then have removed the glass plate and later developed the picture. In essence, Beaman did all the

heavy lifting and someone else merely removed and replaced the lens cap.

The second expedition was better suited for topographic observations. As previously

observed, the first expedition included many Colorado trappers. Of the original ten, only six emerged at the far end.

Hawkins later complained that he and Sumner were stiffed by Powell. According to Hawkins,

Powell promised to pay Hawkins $1.50 a day, reimburse him $960.00 for animals, and pay him $2.50 each for

36 traps which had cost Hawkins $3.00 each. At the end of the journey, Powell gave Hawkins $60.00, not even enough

to reimburse for the traps, let alone the animals or the $1.50 a day for the almost 100 days of the expedition.

Back of stereograph. Start of Powell Expedition.

Back of stereograph. Start of Powell Expedition.

The two Powell Expeditions were the

first to explore the Grand Canyon of the Colorado, a subject beyond the scope of this

website. However, Powell correctly deduced that the Colorado River is really an extension of

Wyoming's Green River, rather than Colorado's "Grand River." In addition to

exploring the Grand Canyon, the expedition produced three of the great western photographers: Beaman

who took the photographs for the first part of the expedition, Fennemore who took the photographs for the

middle part, and finally Hillers who did the final part. As noted above,

Beaman started out as the chief photographer until, as a result of a dispute with

Powell, he was fired. Fennemore, formerly the assistant, then became the chief photographer and

trained Hillers as an assistant. Hillers had originally been employed on the

expedition as an oarsman. Fennemore, himself, had been trained under the great Mormon photographer

C. R. Savage, see Sherman. When Fennemore became ill on the

expedition, Hillers became the chief photographer. Hillers remained with the United States Geologic Survey

until 1919.

Green River City found its salvation when the Black's Fork dried up and there was no water for the

locomotives or the roundhouse operations. The railroad, thus, had to put its tail between its legs

and crawl back to Green River City.

Next page Green River continued.

|